A computer program is a sequence or set of instructions in a programming language for a computer to execute. Computer programs are one component of software, which also includes documentation and other intangible components.[1]

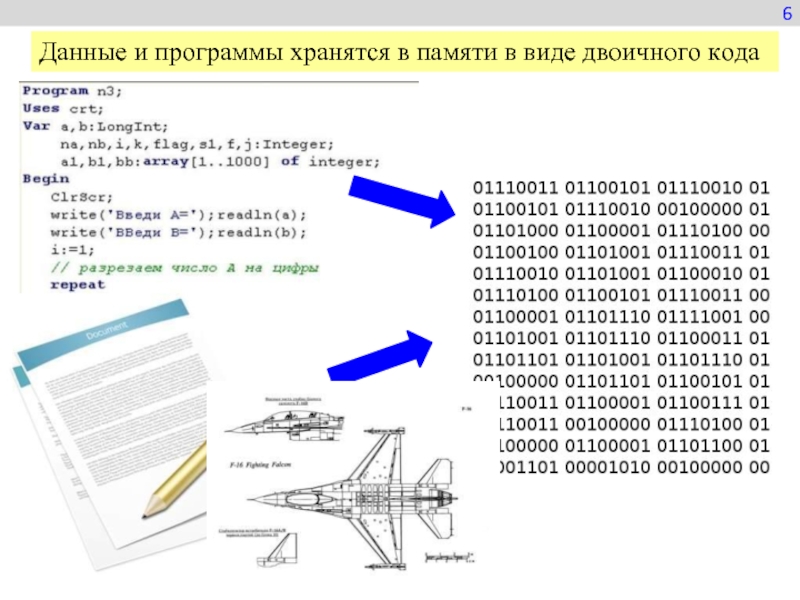

A computer program in its human-readable form is called source code. Source code needs another computer program to execute because computers can only execute their native machine instructions. Therefore, source code may be translated to machine instructions using the language’s compiler. (Assembly language programs are translated using an assembler.) The resulting file is called an executable. Alternatively, source code may execute within the language’s interpreter.[2]

If the executable is requested for execution, then the operating system loads it into memory and starts a process.[3] The central processing unit will soon switch to this process so it can fetch, decode, and then execute each machine instruction.[4]

If the source code is requested for execution, then the operating system loads the corresponding interpreter into memory and starts a process. The interpreter then loads the source code into memory to translate and execute each statement.[2] Running the source code is slower than running an executable.[a] Moreover, the interpreter must be installed on the computer.

Example computer program[edit]

The «Hello, World!» program is used to illustrate a language’s basic syntax. The syntax of the language BASIC (1964) was intentionally limited to make the language easy to learn.[5] For example, variables are not declared before being used.[6] Also, variables are automatically initialized to zero.[6] Here is an example computer program, in Basic, to average a list of numbers:[7]

10 INPUT "How many numbers to average?", A 20 FOR I = 1 TO A 30 INPUT "Enter number:", B 40 LET C = C + B 50 NEXT I 60 LET D = C/A 70 PRINT "The average is", D 80 END

Once the mechanics of basic computer programming are learned, more sophisticated and powerful languages are available to build large computer systems.[8]

History[edit]

Improvements in software development are the result of improvements in computer hardware. At each stage in hardware’s history, the task of computer programming changed dramatically.

Analytical Engine[edit]

In 1837, Charles Babbage was inspired by Jacquard’s loom to attempt to build the Analytical Engine.[9]

The names of the components of the calculating device were borrowed from the textile industry. In the textile industry, yarn was brought from the store to be milled. The device had a «store» which consisted of memory to hold 1,000 numbers of 50 decimal digits each.[10] Numbers from the «store» were transferred to the «mill» for processing. It was programmed using two sets of perforated cards. One set directed the operation and the other set inputted the variables.[9][11] However, after more than 17,000 pounds of the British government’s money, the thousands of cogged wheels and gears never fully worked together.[12]

Ada Lovelace worked for Charles Babbage to create a description of the Analytical Engine (1843).[13] The description contained Note G which completely detailed a method for calculating Bernoulli numbers using the Analytical Engine. This note is recognized by some historians as the world’s first computer program.[12] Other historians consider Babbage himself wrote the first computer program for the Analytical Engine. It listed a sequence of operations to compute the solution for a system of two linear equations.[14]

Universal Turing machine[edit]

In 1936, Alan Turing introduced the Universal Turing machine, a theoretical device that can model every computation.[15]

It is a finite-state machine that has an infinitely long read/write tape. The machine can move the tape back and forth, changing its contents as it performs an algorithm. The machine starts in the initial state, goes through a sequence of steps, and halts when it encounters the halt state.[16] All present-day computers are Turing complete.[17]

ENIAC[edit]

The Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC) was built between July 1943 and Fall 1945. It was a Turing complete, general-purpose computer that used 17,468 vacuum tubes to create the circuits. At its core, it was a series of Pascalines wired together.[18] Its 40 units weighed 30 tons, occupied 1,800 square feet (167 m2), and consumed $650 per hour (in 1940s currency) in electricity when idle.[18] It had 20 base-10 accumulators. Programming the ENIAC took up to two months.[18] Three function tables were on wheels and needed to be rolled to fixed function panels. Function tables were connected to function panels by plugging heavy black cables into plugboards. Each function table had 728 rotating knobs. Programming the ENIAC also involved setting some of the 3,000 switches. Debugging a program took a week.[19] It ran from 1947 until 1955 at Aberdeen Proving Ground, calculating hydrogen bomb parameters, predicting weather patterns, and producing firing tables to aim artillery guns.[20]

Stored-program computers[edit]

Instead of plugging in cords and turning switches, a stored-program computer loads its instructions into memory just like it loads its data into memory.[21] As a result, the computer could be programmed quickly and perform calculations at very fast speeds.[22] Presper Eckert and John Mauchly built the ENIAC. The two engineers introduced the stored-program concept in a three-page memo dated February 1944.[23] Later, in September 1944, Dr. John von Neumann began working on the ENIAC project. On June 30, 1945, von Neumann published the First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC which equated the structures of the computer with the structures of the human brain.[22] The design became known as the von Neumann architecture. The architecture was simultaneously deployed in the constructions of the EDVAC and EDSAC computers in 1949.[24]

The IBM System/360 (1964) was a family of computers, each having the same instruction set architecture. The Model 20 was the smallest and least expensive. Customers could upgrade and retain the same application software.[25] The Model 195 was the most premium. Each System/360 model featured multiprogramming[25]—having multiple processes in memory at once. When one process was waiting for input/output, another could compute.

IBM planned for each model to be programmed using PL/1.[26] A committee was formed that included COBOL, Fortran and ALGOL programmers. The purpose was to develop a language that was comprehensive, easy to use, extendible, and would replace Cobol and Fortran.[26] The result was a large and complex language that took a long time to compile.[27]

Computers manufactured until the 1970s had front-panel switches for manual programming.[28] The computer program was written on paper for reference. An instruction was represented by a configuration of on/off settings. After setting the configuration, an execute button was pressed. This process was then repeated. Computer programs also were automatically inputted via paper tape, punched cards or magnetic-tape. After the medium was loaded, the starting address was set via switches, and the execute button was pressed.[28]

Very Large Scale Integration[edit]

A major milestone in software development was the invention of the Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) circuit (1964).[29] Following World War II, tube-based technology was replaced with point-contact transistors (1947) and bipolar junction transistors (late 1950s) mounted on a circuit board.[29] During the 1960s, the aerospace industry replaced the circuit board with an integrated circuit chip.[29]

Robert Noyce, co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor (1957) and Intel (1968), achieved a technological improvement to refine the production of field-effect transistors (1963).[30] The goal is to alter the electrical resistivity and conductivity of a semiconductor junction. First, naturally occurring silicate minerals are converted into polysilicon rods using the Siemens process.[31] The Czochralski process then converts the rods into a monocrystalline silicon, boule crystal.[32] The crystal is then thinly sliced to form a wafer substrate. The planar process of photolithography then integrates unipolar transistors, capacitors, diodes, and resistors onto the wafer to build a matrix of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) transistors.[33][34] The MOS transistor is the primary component in integrated circuit chips.[30]

Originally, integrated circuit chips had their function set during manufacturing. During the 1960s, controlling the electrical flow migrated to programming a matrix of read-only memory (ROM). The matrix resembled a two-dimensional array of fuses.[29] The process to embed instructions onto the matrix was to burn out the unneeded connections.[29] There were so many connections, firmware programmers wrote a computer program on another chip to oversee the burning.[29] The technology became known as Programmable ROM. In 1971, Intel installed the computer program onto the chip and named it the Intel 4004 microprocessor.[35]

The terms microprocessor and central processing unit (CPU) are now used interchangeably. However, CPUs predate microprocessors. For example, the IBM System/360 (1964) had a CPU made from circuit boards containing discrete components on ceramic substrates.[36]

Sac State 8008[edit]

The Intel 4004 (1971) was a 4-bit microprocessor designed to run the Busicom calculator. Five months after its release, Intel released the Intel 8008, an 8-bit microprocessor. Bill Pentz led a team at Sacramento State to build the first microcomputer using the Intel 8008: the Sac State 8008 (1972).[37] Its purpose was to store patient medical records. The computer supported a disk operating system to run a Memorex, 3-megabyte, hard disk drive.[29] It had a color display and keyboard that was packaged in a single console. The disk operating system was programmed using IBM’s Basic Assembly Language (BAL). The medical records application was programmed using a BASIC interpreter.[29] However, the computer was an evolutionary dead-end because it was extremely expensive. Also, it was built at a public university lab for a specific purpose.[37] Nonetheless, the project contributed to the development of the Intel 8080 (1974) instruction set.[29]

x86 series[edit]

In 1978, the modern software development environment began when Intel upgraded the Intel 8080 to the Intel 8086. Intel simplified the Intel 8086 to manufacture the cheaper Intel 8088.[38] IBM embraced the Intel 8088 when they entered the personal computer market (1981). As consumer demand for personal computers increased, so did Intel’s microprocessor development. The succession of development is known as the x86 series. The x86 assembly language is a family of backward-compatible machine instructions. Machine instructions created in earlier microprocessors were retained throughout microprocessor upgrades. This enabled consumers to purchase new computers without having to purchase new application software. The major categories of instructions are:[b]

- Memory instructions to set and access numbers and strings in random-access memory.

- Integer arithmetic logic unit (ALU) instructions to perform the primary arithmetic operations on integers.

- Floating point ALU instructions to perform the primary arithmetic operations on real numbers.

- Call stack instructions to push and pop words needed to allocate memory and interface with functions.

- Single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) instructions[c] to increase speed when multiple processors are available to perform the same algorithm on an array of data.

Changing programming environment[edit]

VLSI circuits enabled the programming environment to advance from a computer terminal (until the 1990s) to a graphical user interface (GUI) computer. Computer terminals limited programmers to a single shell running in a command-line environment. During the 1970s, full-screen source code editing became possible through a text-based user interface. Regardless of the technology available, the goal is to program in a programming language.

Programming paradigms and languages[edit]

Programming language features exist to provide building blocks to be combined to express programming ideals.[39] Ideally, a programming language should:[39]

- express ideas directly in the code.

- express independent ideas independently.

- express relationships among ideas directly in the code.

- combine ideas freely.

- combine ideas only where combinations make sense.

- express simple ideas simply.

The programming style of a programming language to provide these building blocks may be categorized into programming paradigms.[40] For example, different paradigms may differentiate:[40]

- procedural languages, functional languages, and logical languages.

- different levels of data abstraction.

- different levels of class hierarchy.

- different levels of input datatypes, as in container types and generic programming.

Each of these programming styles has contributed to the synthesis of different programming languages.[40]

A programming language is a set of keywords, symbols, identifiers, and rules by which programmers can communicate instructions to the computer.[41] They follow a set of rules called a syntax.[41]

- Keywords are reserved words to form declarations and statements.

- Symbols are characters to form operations, assignments, control flow, and delimiters.

- Identifiers are words created by programmers to form constants, variable names, structure names, and function names.

- Syntax Rules are defined in the Backus–Naur form.

Programming languages get their basis from formal languages.[42] The purpose of defining a solution in terms of its formal language is to generate an algorithm to solve the underlining problem.[42] An algorithm is a sequence of simple instructions that solve a problem.[43]

Generations of programming language[edit]

The evolution of programming language began when the EDSAC (1949) used the first stored computer program in its von Neumann architecture.[44] Programming the EDSAC was in the first generation of programming language.

- The first generation of programming language is machine language.[45] Machine language requires the programmer to enter instructions using instruction numbers called machine code. For example, the ADD operation on the PDP-11 has instruction number 24576.[46]

- The second generation of programming language is assembly language.[45] Assembly language allows the programmer to use mnemonic instructions instead of remembering instruction numbers. An assembler translates each assembly language mnemonic into its machine language number. For example, on the PDP-11, the operation 24576 can be referenced as ADD in the source code.[46] The four basic arithmetic operations have assembly instructions like ADD, SUB, MUL, and DIV.[46] Computers also have instructions like DW (Define Word) to reserve memory cells. Then the MOV instruction can copy integers between registers and memory.

-

- The basic structure of an assembly language statement is a label, operation, operand, and comment.[47]

-

- Labels allow the programmer to work with variable names. The assembler will later translate labels into physical memory addresses.

- Operations allow the programmer to work with mnemonics. The assembler will later translate mnemonics into instruction numbers.

- Operands tell the assembler which data the operation will process.

- Comments allow the programmer to articulate a narrative because the instructions alone are vague.

- The key characteristic of an assembly language program is it forms a one-to-one mapping to its corresponding machine language target.[48]

- The third generation of programming language uses compilers and interpreters to execute computer programs. The distinguishing feature of a third generation language is its independence from particular hardware.[49] Early languages include Fortran (1958), COBOL (1959), ALGOL (1960), and BASIC (1964).[45] In 1973, the C programming language emerged as a high-level language that produced efficient machine language instructions.[50] Whereas third-generation languages historically generated many machine instructions for each statement,[51] C has statements that may generate a single machine instruction.[d] Moreover, an optimizing compiler might overrule the programmer and produce fewer machine instructions than statements. Today, an entire paradigm of languages fill the imperative, third generation spectrum.

- The fourth generation of programming language emphasizes what output results are desired, rather than how programming statements should be constructed.[45] Declarative languages attempt to limit side effects and allow programmers to write code with relatively few errors.[45] One popular fourth generation language is called Structured Query Language (SQL).[45] Database developers no longer need to process each database record one at a time. Also, a simple instruction can generate output records without having to understand how it’s retrieved.

Imperative languages[edit]

Imperative languages specify a sequential algorithm using declarations, expressions, and statements:[52]

- A declaration introduces a variable name to the computer program and assigns it to a datatype[53] – for example:

var x: integer; - An expression yields a value – for example:

2 + 2yields 4 - A statement might assign an expression to a variable or use the value of a variable to alter the program’s control flow – for example:

x := 2 + 2; if x = 4 then do_something();

Fortran[edit]

FORTRAN (1958) was unveiled as «The IBM Mathematical FORmula TRANslating system.» It was designed for scientific calculations, without string handling facilities. Along with declarations, expressions, and statements, it supported:

- arrays.

- subroutines.

- «do» loops.

It succeeded because:

- programming and debugging costs were below computer running costs.

- it was supported by IBM.

- applications at the time were scientific.[54]

However, non-IBM vendors also wrote Fortran compilers, but with a syntax that would likely fail IBM’s compiler.[54] The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) developed the first Fortran standard in 1966. In 1978, Fortran 77 became the standard until 1991. Fortran 90 supports:

- records.

- pointers to arrays.

COBOL[edit]

COBOL (1959) stands for «COmmon Business Oriented Language.» Fortran manipulated symbols. It was soon realized that symbols didn’t need to be numbers, so strings were introduced.[55] The US Department of Defense influenced COBOL’s development, with Grace Hopper being a major contributor. The statements were English-like and verbose. The goal was to design a language so managers could read the programs. However, the lack of structured statements hindered this goal.[56]

COBOL’s development was tightly controlled, so dialects didn’t emerge to require ANSI standards. As a consequence, it wasn’t changed for 15 years until 1974. The 1990s version did make consequential changes, like object-oriented programming.[56]

Algol[edit]

ALGOL (1960) stands for «ALGOrithmic Language.» It had a profound influence on programming language design.[57] Emerging from a committee of European and American programming language experts, it used standard mathematical notation and had a readable structured design. Algol was first to define its syntax using the Backus–Naur form.[57] This led to syntax-directed compilers. It added features like:

- block structure, where variables were local to their block.

- arrays with variable bounds.

- «for» loops.

- functions.

- recursion.[57]

Algol’s direct descendants include Pascal, Modula-2, Ada, Delphi and Oberon on one branch. On another branch the descendants include C, C++ and Java.[57]

Basic[edit]

BASIC (1964) stands for «Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code.» It was developed at Dartmouth College for all of their students to learn.[7] If a student didn’t go on to a more powerful language, the student would still remember Basic.[7] A Basic interpreter was installed in the microcomputers manufactured in the late 1970s. As the microcomputer industry grew, so did the language.[7]

Basic pioneered the interactive session.[7] It offered operating system commands within its environment:

- The ‘new’ command created an empty slate.

- Statements evaluated immediately.

- Statements could be programmed by preceding them with a line number.

- The ‘list’ command displayed the program.

- The ‘run’ command executed the program.

However, the Basic syntax was too simple for large programs.[7] Recent dialects added structure and object-oriented extensions. Microsoft’s Visual Basic is still widely used and produces a graphical user interface.[6]

C[edit]

C programming language (1973) got its name because the language BCPL was replaced with B, and AT&T Bell Labs called the next version «C.» Its purpose was to write the UNIX operating system.[50] C is a relatively small language, making it easy to write compilers. Its growth mirrored the hardware growth in the 1980s.[50] Its growth also was because it has the facilities of assembly language, but uses a high-level syntax. It added advanced features like:

- inline assembler.

- arithmetic on pointers.

- pointers to functions.

- bit operations.

- freely combining complex operators.[50]

C allows the programmer to control which region of memory data is to be stored. Global variables and static variables require the fewest clock cycles to store. The stack is automatically used for the standard variable declarations. Heap memory is returned to a pointer variable from the malloc() function.

- The global and static data region is located just above the program region. (The program region is technically called the text region. It’s where machine instructions are stored.)

-

- The global and static data region is technically two regions.[58] One region is called the initialized data segment, where variables declared with default values are stored. The other region is called the block started by segment, where variables declared without default values are stored.

- Variables stored in the global and static data region have their addresses set at compile-time. They retain their values throughout the life of the process.

-

- The global and static region stores the global variables that are declared on top of (outside) the

main()function.[59] Global variables are visible tomain()and every other function in the source code.

- The global and static region stores the global variables that are declared on top of (outside) the

- On the other hand, variable declarations inside of

main(), other functions, or within{}block delimiters are local variables. Local variables also include formal parameter variables. Parameter variables are enclosed within the parenthesis of function definitions.[60] They provide an interface to the function.

-

- Local variables declared using the

staticprefix are also stored in the global and static data region.[58] Unlike global variables, static variables are only visible within the function or block. Static variables always retain their value. An example usage would be the functionint increment_counter(){ static int counter = 0; counter++; return counter;}

- Local variables declared using the

- The stack region is a contiguous block of memory located near the top memory address.[61] Variables placed in the stack are populated from top to bottom.[e][61] A stack pointer is a special-purpose register that keeps track of the last memory address populated.[61] Variables are placed into the stack via the assembly language PUSH instruction. Therefore, the addresses of these variables are set during runtime. The method for stack variables to lose their scope is via the POP instruction.

-

- Local variables declared without the

staticprefix, including formal parameter variables,[62] are called automatic variables[59] and are stored in the stack.[58] They are visible inside the function or block and lose their scope upon exiting the function or block.

- Local variables declared without the

- The heap region is located below the stack.[58] It is populated from the bottom to the top. The operating system manages the heap using a heap pointer and a list of allocated memory blocks.[63] Like the stack, the addresses of heap variables are set during runtime. An out of memory error occurs when the heap pointer and the stack pointer meet.

-

- C provides the

malloc()library function to allocate heap memory.[64] Populating the heap with data is an additional copy function. Variables stored in the heap are economically passed to functions using pointers. Without pointers, the entire block of data would have to be passed to the function via the stack.

- C provides the

C++[edit]

In the 1970s, software engineers needed language support to break large projects down into modules.[65] One obvious feature was to decompose large projects physically into separate files. A less obvious feature was to decompose large projects logically into abstract datatypes.[65] At the time, languages supported concrete (scalar) datatypes like integer numbers, floating-point numbers, and strings of characters. Concrete datatypes have their representation as part of their name.[66] Abstract datatypes are structures of concrete datatypes, with a new name assigned. For example, a list of integers could be called integer_list.

In object-oriented jargon, abstract datatypes are called classes. However, a class is only a definition; no memory is allocated. When memory is allocated to a class and bound to an identifier, it’s called an object.[67]

Object-oriented imperative languages developed by combining the need for classes and the need for safe functional programming.[68] A function, in an object-oriented language, is assigned to a class. An assigned function is then referred to as a method, member function, or operation. Object-oriented programming is executing operations on objects.[69]

Object-oriented languages support a syntax to model subset/superset relationships. In set theory, an element of a subset inherits all the attributes contained in the superset. For example, a student is a person. Therefore, the set of students is a subset of the set of persons. As a result, students inherit all the attributes common to all persons. Additionally, students have unique attributes that other people don’t have. Object-oriented languages model subset/superset relationships using inheritance.[70] Object-oriented programming became the dominant language paradigm by the late 1990s.[65]

C++ (1985) was originally called «C with Classes.»[71] It was designed to expand C’s capabilities by adding the object-oriented facilities of the language Simula.[72]

An object-oriented module is composed of two files. The definitions file is called the header file. Here is a C++ header file for the GRADE class in a simple school application:

// grade.h // ------- // Used to allow multiple source files to include // this header file without duplication errors. // ---------------------------------------------- #ifndef GRADE_H #define GRADE_H class GRADE { public: // This is the constructor operation. // ---------------------------------- GRADE ( const char letter ); // This is a class variable. // ------------------------- char letter; // This is a member operation. // --------------------------- int grade_numeric( const char letter ); // This is a class variable. // ------------------------- int numeric; }; #endif

A constructor operation is a function with the same name as the class name.[73] It is executed when the calling operation executes the new statement.

A module’s other file is the source file. Here is a C++ source file for the GRADE class in a simple school application:

// grade.cpp // --------- #include "grade.h" GRADE::GRADE( const char letter ) { // Reference the object using the keyword 'this'. // ---------------------------------------------- this->letter = letter; // This is Temporal Cohesion // ------------------------- this->numeric = grade_numeric( letter ); } int GRADE::grade_numeric( const char letter ) { if ( ( letter == 'A' || letter == 'a' ) ) return 4; else if ( ( letter == 'B' || letter == 'b' ) ) return 3; else if ( ( letter == 'C' || letter == 'c' ) ) return 2; else if ( ( letter == 'D' || letter == 'd' ) ) return 1; else if ( ( letter == 'F' || letter == 'f' ) ) return 0; else return -1; }

Here is a C++ header file for the PERSON class in a simple school application:

// person.h // -------- #ifndef PERSON_H #define PERSON_H class PERSON { public: PERSON ( const char *name ); const char *name; }; #endif

Here is a C++ source file for the PERSON class in a simple school application:

// person.cpp // ---------- #include "person.h" PERSON::PERSON ( const char *name ) { this->name = name; }

Here is a C++ header file for the STUDENT class in a simple school application:

// student.h // --------- #ifndef STUDENT_H #define STUDENT_H #include "person.h" #include "grade.h" // A STUDENT is a subset of PERSON. // -------------------------------- class STUDENT : public PERSON{ public: STUDENT ( const char *name ); GRADE *grade; }; #endif

Here is a C++ source file for the STUDENT class in a simple school application:

// student.cpp // ----------- #include "student.h" #include "person.h" STUDENT::STUDENT ( const char *name ): // Execute the constructor of the PERSON superclass. // ------------------------------------------------- PERSON( name ) { // Nothing else to do. // ------------------- }

Here is a driver program for demonstration:

// student_dvr.cpp // --------------- #include <iostream> #include "student.h" int main( void ) { STUDENT *student = new STUDENT( "The Student" ); student->grade = new GRADE( 'a' ); std::cout // Notice student inherits PERSON's name << student->name << ": Numeric grade =" << student->grade->numeric << "n"; return 0; }

Here is a makefile to compile everything:

# makefile # -------- all: student_dvr clean: rm student_dvr *.o student_dvr: student_dvr.cpp grade.o student.o person.o c++ student_dvr.cpp grade.o student.o person.o -o student_dvr grade.o: grade.cpp grade.h c++ -c grade.cpp student.o: student.cpp student.h c++ -c student.cpp person.o: person.cpp person.h c++ -c person.cpp

Declarative languages[edit]

Imperative languages have one major criticism: assigning an expression to a non-local variable may produce an unintended side effect.[74] Declarative languages generally omit the assignment statement and the control flow. They describe what computation should be performed and not how to compute it. Two broad categories of declarative languages are functional languages and logical languages.

The principle behind a functional language is to use lambda calculus as a guide for a well defined semantic.[75] In mathematics, a function is a rule that maps elements from an expression to a range of values. Consider the function:

times_10(x) = 10 * x

The expression 10 * x is mapped by the function times_10() to a range of values. One value happens to be 20. This occurs when x is 2. So, the application of the function is mathematically written as:

times_10(2) = 20

A functional language compiler will not store this value in a variable. Instead, it will push the value onto the computer’s stack before setting the program counter back to the calling function. The calling function will then pop the value from the stack.[76]

Imperative languages do support functions. Therefore, functional programming can be achieved in an imperative language, if the programmer uses discipline. However, a functional language will force this discipline onto the programmer through its syntax. Functional languages have a syntax tailored to emphasize the what.[77]

A functional program is developed with a set of primitive functions followed by a single driver function.[74] Consider the snippet:

function max(a,b){/* code omitted */}

function min(a,b){/* code omitted */}

function difference_between_largest_and_smallest(a,b,c) {

return max(a,max(b,c)) - min(a, min(b,c));

}

The primitives are max() and min(). The driver function is difference_between_largest_and_smallest(). Executing:

put(difference_between_largest_and_smallest(10,4,7)); will output 6.

Functional languages are used in computer science research to explore new language features.[78] Moreover, their lack of side-effects have made them popular in parallel programming and concurrent programming.[79] However, application developers prefer the object-oriented features of imperative languages.[79]

Lisp[edit]

Lisp (1958) stands for «LISt Processor.»[80] It is tailored to process lists. A full structure of the data is formed by building lists of lists. In memory, a tree data structure is built. Internally, the tree structure lends nicely for recursive functions.[81] The syntax to build a tree is to enclose the space-separated elements within parenthesis. The following is a list of three elements. The first two elements are themselves lists of two elements:

((A B) (HELLO WORLD) 94)

Lisp has functions to extract and reconstruct elements.[82] The function head() returns a list containing the first element in the list. The function tail() returns a list containing everything but the first element. The function cons() returns a list that is the concatenation of other lists. Therefore, the following expression will return the list x:

cons(head(x), tail(x))

One drawback of Lisp is when many functions are nested, the parentheses may look confusing.[77] Modern Lisp environments help ensure parenthesis match. As an aside, Lisp does support the imperative language operations of the assignment statement and goto loops.[83] Also, Lisp is not concerned with the datatype of the elements at compile time.[84] Instead, it assigns (and may reassign) the datatypes at runtime. Assigning the datatype at runtime is called dynamic binding.[85] Whereas dynamic binding increases the language’s flexibility, programming errors may linger until late in the software development process.[85]

Writing large, reliable, and readable Lisp programs requires forethought. If properly planned, the program may be much shorter than an equivalent imperative language program.[77] Lisp is widely used in artificial intelligence. However, its usage has been accepted only because it has imperative language operations, making unintended side-effects possible.[79]

ML[edit]

ML (1973)[86] stands for «Meta Language.» ML checks to make sure only data of the same type are compared with one another.[87] For example, this function has one input parameter (an integer) and returns an integer:

fun times_10(n : int) : int = 10 * n;

ML is not parenthesis-eccentric like Lisp. The following is an application of times_10():

times_10 2

It returns «20 : int». (Both the results and the datatype are returned.)

Like Lisp, ML is tailored to process lists. Unlike Lisp, each element is the same datatype.[88] Moreover, ML assigns the datatype of an element at compile-time. Assigning the datatype at compile-time is called static binding. Static binding increases reliability because the compiler checks the context of variables before they are used.[89]

Prolog[edit]

Prolog (1972) stands for «PROgramming in LOgic.» It was designed to process natural languages.[90] The building blocks of a Prolog program are objects and their relationships to other objects. Objects are built by stating true facts about them.[91]

Set theory facts are formed by assigning objects to sets. The syntax is setName(object).

- Cat is an animal.

animal(cat).

- Mouse is an animal.

animal(mouse).

- Tom is a cat.

cat(tom).

- Jerry is a mouse.

mouse(jerry).

Adjective facts are formed using adjective(object).

- Cat is big.

big(cat).

- Mouse is small.

small(mouse).

Relationships are formed using multiple items inside the parentheses. In our example we have verb(object,object) and verb(adjective,adjective).

- Mouse eats cheese.

eat(mouse,cheese).

- Big animals eat small animals.

eat(big,small).

After all the facts and relationships are entered, then a question can be asked:

- Will Tom eat Jerry?

?- eat(tom,jerry).

Prolog’s usage has expanded to become a goal-oriented language.[92] In a goal-oriented application, the goal is defined by providing a list of subgoals. Then each subgoal is defined by further providing a list of its subgoals, etc. If a path of subgoals fails to find a solution, then that subgoal is backtracked and another path is systematically attempted.[91] Practical applications include solving the shortest path problem[90] and producing family trees.[93]

Object-oriented programming[edit]

Object-oriented programming is a programming method to execute operations (functions) on objects.[94] The basic idea is to group the characteristics of a phenomenon into an object container and give the container a name. The operations on the phenomenon are also grouped into the container.[94] Object-oriented programming developed by combining the need for containers and the need for safe functional programming.[95] This programming method need not be confined to an object-oriented language.[96] In an object-oriented language, an object container is called a class. In a non-object-oriented language, a data structure (which is also known as a record) may become an object container. To turn a data structure into an object container, operations need to be written specifically for the structure. The resulting structure is called an abstract datatype.[97] However, inheritance will be missing. Nonetheless, this shortcoming can be overcome.

Here is a C programming language header file for the GRADE abstract datatype in a simple school application:

/* grade.h */ /* ------- */ /* Used to allow multiple source files to include */ /* this header file without duplication errors. */ /* ---------------------------------------------- */ #ifndef GRADE_H #define GRADE_H typedef struct { char letter; } GRADE; /* Constructor */ /* ----------- */ GRADE *grade_new( char letter ); int grade_numeric( char letter ); #endif

The grade_new() function performs the same algorithm as the C++ constructor operation.

Here is a C programming language source file for the GRADE abstract datatype in a simple school application:

/* grade.c */ /* ------- */ #include "grade.h" GRADE *grade_new( char letter ) { GRADE *grade; /* Allocate heap memory */ /* -------------------- */ if ( ! ( grade = calloc( 1, sizeof ( GRADE ) ) ) ) { fprintf(stderr, "ERROR in %s/%s/%d: calloc() returned empty.n", __FILE__, __FUNCTION__, __LINE__ ); exit( 1 ); } grade->letter = letter; return grade; } int grade_numeric( char letter ) { if ( ( letter == 'A' || letter == 'a' ) ) return 4; else if ( ( letter == 'B' || letter == 'b' ) ) return 3; else if ( ( letter == 'C' || letter == 'c' ) ) return 2; else if ( ( letter == 'D' || letter == 'd' ) ) return 1; else if ( ( letter == 'F' || letter == 'f' ) ) return 0; else return -1; }

In the constructor, the function calloc() is used instead of malloc() because each memory cell will be set to zero.

Here is a C programming language header file for the PERSON abstract datatype in a simple school application:

/* person.h */ /* -------- */ #ifndef PERSON_H #define PERSON_H typedef struct { char *name; } PERSON; /* Constructor */ /* ----------- */ PERSON *person_new( char *name ); #endif

Here is a C programming language source file for the PERSON abstract datatype in a simple school application:

/* person.c */ /* -------- */ #include "person.h" PERSON *person_new( char *name ) { PERSON *person; if ( ! ( person = calloc( 1, sizeof ( PERSON ) ) ) ) { fprintf(stderr, "ERROR in %s/%s/%d: calloc() returned empty.n", __FILE__, __FUNCTION__, __LINE__ ); exit( 1 ); } person->name = name; return person; }

Here is a C programming language header file for the STUDENT abstract datatype in a simple school application:

/* student.h */ /* --------- */ #ifndef STUDENT_H #define STUDENT_H #include "person.h" #include "grade.h" typedef struct { /* A STUDENT is a subset of PERSON. */ /* -------------------------------- */ PERSON *person; GRADE *grade; } STUDENT; /* Constructor */ /* ----------- */ STUDENT *student_new( char *name ); #endif

Here is a C programming language source file for the STUDENT abstract datatype in a simple school application:

/* student.c */ /* --------- */ #include "student.h" #include "person.h" STUDENT *student_new( char *name ) { STUDENT *student; if ( ! ( student = calloc( 1, sizeof ( STUDENT ) ) ) ) { fprintf(stderr, "ERROR in %s/%s/%d: calloc() returned empty.n", __FILE__, __FUNCTION__, __LINE__ ); exit( 1 ); } /* Execute the constructor of the PERSON superclass. */ /* ------------------------------------------------- */ student->person = person_new( name ); return student; }

Here is a driver program for demonstration:

/* student_dvr.c */ /* ------------- */ #include <stdio.h> #include "student.h" int main( void ) { STUDENT *student = student_new( "The Student" ); student->grade = grade_new( 'a' ); printf( "%s: Numeric grade = %dn", /* Whereas a subset exists, inheritance does not. */ student->person->name, /* Functional programming is executing functions just-in-time (JIT) */ grade_numeric( student->grade->letter ) ); return 0; }

Here is a makefile to compile everything:

# makefile # -------- all: student_dvr clean: rm student_dvr *.o student_dvr: student_dvr.c grade.o student.o person.o gcc student_dvr.c grade.o student.o person.o -o student_dvr grade.o: grade.c grade.h gcc -c grade.c student.o: student.c student.h gcc -c student.c person.o: person.c person.h gcc -c person.c

The formal strategy to build object-oriented objects is to:[98]

- Identify the objects. Most likely these will be nouns.

- Identify each object’s attributes. What helps to describe the object?

- Identify each object’s actions. Most likely these will be verbs.

- Identify the relationships from object to object. Most likely these will be verbs.

For example:

- A person is a human identified by a name.

- A grade is an achievement identified by a letter.

- A student is a person who earns a grade.

Syntax and semantics[edit]

The syntax of a programming language is a list of production rules which govern its form.[99] A programming language’s form is the correct placement of its declarations, expressions, and statements.[100] Complementing the syntax of a language are its semantics. The semantics describe the meanings attached to various syntactic constructs.[99] A syntactic construct may need a semantic description because a form may have an invalid interpretation.[101] Also, different languages might have the same syntax; however, their behaviors may be different.

The syntax of a language is formally described by listing the production rules. Whereas the syntax of a natural language is extremely complicated, a subset of the English language can have this production rule listing:[102]

- a sentence is made up of a noun-phrase followed by a verb-phrase;

- a noun-phrase is made up of an article followed by an adjective followed by a noun;

- a verb-phrase is made up of a verb followed by a noun-phrase;

- an article is ‘the’;

- an adjective is ‘big’ or

- an adjective is ‘small’;

- a noun is ‘cat’ or

- a noun is ‘mouse’;

- a verb is ‘eats’;

The words in bold-face are known as «non-terminals». The words in ‘single quotes’ are known as «terminals».[103]

From this production rule listing, complete sentences may be formed using a series of replacements.[104] The process is to replace non-terminals with either a valid non-terminal or a valid terminal. The replacement process repeats until only terminals remain. One valid sentence is:

- sentence

- noun-phrase verb-phrase

- article adjective noun verb-phrase

- the adjective noun verb-phrase

- the big noun verb-phrase

- the big cat verb-phrase

- the big cat verb noun-phrase

- the big cat eats noun-phrase

- the big cat eats article adjective noun

- the big cat eats the adjective noun

- the big cat eats the small noun

- the big cat eats the small mouse

However, another combination results in an invalid sentence:

- the small mouse eats the big cat

Therefore, a semantic is necessary to correctly describe the meaning of an eat activity.

One production rule listing method is called the Backus–Naur form (BNF).[105] BNF describes the syntax of a language and itself has a syntax. This recursive definition is an example of a meta-language.[99] The syntax of BNF includes:

::=which translates to is made up of a[n] when a non-terminal is to its right. It translates to is when a terminal is to its right.|which translates to or.<and>which surround non-terminals.

Using BNF, a subset of the English language can have this production rule listing:

<sentence> ::= <noun-phrase><verb-phrase> <noun-phrase> ::= <article><adjective><noun> <verb-phrase> ::= <verb><noun-phrase> <article> ::= the <adjective> ::= big | small <noun> ::= cat | mouse <verb> ::= eats

Using BNF, a signed-integer has the production rule listing:[106]

<signed-integer> ::= <sign><integer> <sign> ::= + | - <integer> ::= <digit> | <digit><integer> <digit> ::= 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Notice the recursive production rule:

<integer> ::= <digit> | <digit><integer>

This allows for an infinite number of possibilities. Therefore, a semantic is necessary to describe a limitation of the number of digits.

Notice the leading zero possibility in the production rules:

<integer> ::= <digit> | <digit><integer> <digit> ::= 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Therefore, a semantic is necessary to describe that leading zeros need to be ignored.

Two formal methods are available to describe semantics. They are denotational semantics and axiomatic semantics.[107]

Software engineering and computer programming[edit]

Software engineering is a variety of techniques to produce quality software.[108] Computer programming is the process of writing or editing source code. In a formal environment, a systems analyst will gather information from managers about all the organization’s processes to automate. This professional then prepares a detailed plan for the new or modified system.[109] The plan is analogous to an architect’s blueprint.[109]

Performance objectives[edit]

The systems analyst has the objective to deliver the right information to the right person at the right time.[110] The critical factors to achieve this objective are:[110]

- The quality of the output. Is the output useful for decision-making?

- The accuracy of the output. Does it reflect the true situation?

- The format of the output. Is the output easily understood?

- The speed of the output. Time-sensitive information is important when communicating with the customer in real time.

Cost objectives[edit]

Achieving performance objectives should be balanced with all of the costs, including:[111]

- Development costs.

- Uniqueness costs. A reusable system may be expensive. However, it might be preferred over a limited-use system.

- Hardware costs.

- Operating costs.

Applying a systems development process will mitigate the axiom: the later in the process an error is detected, the more expensive it is to correct.[112]

Waterfall model[edit]

The waterfall model is an implementation of a systems development process.[113] As the waterfall label implies, the basic phases overlap each other:[114]

- The investigation phase is to understand the underlying problem.

- The analysis phase is to understand the possible solutions.

- The design phase is to plan the best solution.

- The implementation phase is to program the best solution.

- The maintenance phase lasts throughout the life of the system. Changes to the system after it’s deployed may be necessary.[115] Faults may exist, including specification faults, design faults, or coding faults. Improvements may be necessary. Adaption may be necessary to react to a changing environment.

Computer programmer[edit]

A computer programmer is a specialist responsible for writing or modifying the source code to implement the detailed plan.[109] A programming team is likely to be needed because most systems are too large to be completed by a single programmer.[116] However, adding programmers to a project may not shorten the completion time. Instead, it may lower the quality of the system.[116] To be effective, program modules need to be defined and distributed to team members.[116] Also, team members must interact with one another in a meaningful and effective way.[116]

Computer programmers may be programming-in-the-small: programming within a single module.[117] Chances are a module will execute modules located in other source code files. Therefore, computer programmers may be programming-in-the-large: programming modules so they will effectively couple with each other.[117] Programming-in-the-large includes contributing to the application programming interface (API).

Program modules[edit]

Modular programming is a technique to refine imperative language programs. Refined programs may reduce the software size, separate responsibilities, and thereby mitigate software aging. A program module is a sequence of statements that are bounded within a block and together identified by a name.[118] Modules have a function, context, and logic:[119]

- The function of a module is what it does.

- The context of a module are the elements being performed upon.

- The logic of a module is how it performs the function.

The module’s name should be derived first by its function, then by its context. Its logic should not be part of the name.[119] For example, function compute_square_root( x ) or function compute_square_root_integer( i : integer ) are appropriate module names. However, function compute_square_root_by_division( x ) is not.

The degree of interaction within a module is its level of cohesion.[119] Cohesion is a judgment of the relationship between a module’s name and its function. The degree of interaction between modules is the level of coupling.[120] Coupling is a judgement of the relationship between a module’s context and the elements being performed upon.

Cohesion[edit]

The levels of cohesion from worst to best are:[121]

- Coincidental Cohesion: A module has coincidental cohesion if it performs multiple functions, and the functions are completely unrelated. For example,

function read_sales_record_print_next_line_convert_to_float(). Coincidental cohesion occurs in practice if management enforces silly rules. For example, «Every module will have between 35 and 50 executable statements.»[121] - Logical Cohesion: A module has logical cohesion if it has available a series of functions, but only one of them is executed. For example,

function perform_arithmetic( perform_addition, a, b ). - Temporal Cohesion: A module has temporal cohesion if it performs functions related to time. One example,

function initialize_variables_and_open_files(). Another example,stage_one(),stage_two(), … - Procedural Cohesion: A module has procedural cohesion if it performs multiple loosely related functions. For example,

function read_part_number_update_employee_record(). - Communicational Cohesion: A module has communicational cohesion if it performs multiple closely related functions. For example,

function read_part_number_update_sales_record(). - Informational Cohesion: A module has informational cohesion if it performs multiple functions, but each function has its own entry and exit points. Moreover, the functions share the same data structure. Object-oriented classes work at this level.

- Functional Cohesion: a module has functional cohesion if it achieves a single goal working only on local variables. Moreover, it may be reusable in other contexts.

Coupling[edit]

The levels of coupling from worst to best are:[120]

- Content Coupling: A module has content coupling if it modifies a local variable of another function. COBOL used to do this with the alter verb.

- Common Coupling: A module has common coupling if it modifies a global variable.

- Control Coupling: A module has control coupling if another module can modify its control flow. For example,

perform_arithmetic( perform_addition, a, b ). Instead, control should be on the makeup of the returned object. - Stamp Coupling: A module has stamp coupling if an element of a data structure passed as a parameter is modified. Object-oriented classes work at this level.

- Data Coupling: A module has data coupling if all of its input parameters are needed and none of them are modified. Moreover, the result of the function is returned as a single object.

Data flow analysis[edit]

Data flow analysis is a design method used to achieve modules of functional cohesion and data coupling.[122] The input to the method is a data-flow diagram. A data-flow diagram is a set of ovals representing modules. Each module’s name is displayed inside its oval. Modules may be at the executable level or the function level.

The diagram also has arrows connecting modules to each other. Arrows pointing into modules represent a set of inputs. Each module should have only one arrow pointing out from it to represent its single output object. (Optionally, an additional exception arrow points out.) A daisy chain of ovals will convey an entire algorithm. The input modules should start the diagram. The input modules should connect to the transform modules. The transform modules should connect to the output modules.[123]

Functional categories[edit]

Computer programs may be categorized along functional lines. The main functional categories are application software and system software. System software includes the operating system, which couples computer hardware with application software.[124] The purpose of the operating system is to provide an environment where application software executes in a convenient and efficient manner.[124] Both application software and system software execute utility programs. At the hardware level, a microcode program controls the circuits throughout the central processing unit.

Application software[edit]

Application software is the key to unlocking the potential of the computer system.[125] Enterprise application software bundles accounting, personnel, customer, and vendor applications. Examples include enterprise resource planning, customer relationship management, and supply chain management software.

Enterprise applications may be developed in-house as a one-of-a-kind proprietary software.[126] Alternatively, they may be purchased as off-the-shelf software. Purchased software may be modified to provide custom software. If the application is customized, then either the company’s resources are used or the resources are outsourced. Outsourced software development may be from the original software vendor or a third-party developer.[127]

The potential advantages of in-house software are features and reports may be developed exactly to specification.[128] Management may also be involved in the development process and offer a level of control.[129] Management may decide to counteract a competitor’s new initiative or implement a customer or vendor requirement.[130] A merger or acquisition may necessitate enterprise software changes. The potential disadvantages of in-house software are time and resource costs may be extensive.[126] Furthermore, risks concerning features and performance may be looming.

The potential advantages of off-the-shelf software are upfront costs are identifiable, the basic needs should be fulfilled, and its performance and reliability have a track record.[126] The potential disadvantages of off-the-shelf software are it may have unnecessary features that confuse end users, it may lack features the enterprise needs, and the data flow may not match the enterprise’s work processes.[126]

One approach to economically obtaining a customized enterprise application is through an application service provider.[131] Specialty companies provide hardware, custom software, and end-user support. They may speed the development of new applications because they possess skilled information system staff. The biggest advantage is it frees in-house resources from staffing and managing complex computer projects.[131] Many application service providers target small, fast-growing companies with limited information system resources.[131] On the other hand, larger companies with major systems will likely have their technical infrastructure in place. One risk is having to trust an external organization with sensitive information. Another risk is having to trust the provider’s infrastructure reliability.[131]

Operating system[edit]

Scheduling, Preemption, Context Switching

An operating system is the low-level software that supports a computer’s basic functions, such as scheduling processes and controlling peripherals.[124]

In the 1950s, the programmer, who was also the operator, would write a program and run it. After the program finished executing, the output may have been printed, or it may have been punched onto paper tape or cards for later processing.[28] More often than not the program did not work. The programmer then looked at the console lights and fiddled with the console switches. If less fortunate, a memory printout was made for further study. In the 1960s, programmers reduced the amount of wasted time by automating the operator’s job. A program called an operating system was kept in the computer at all times.[132]

The term operating system may refer to two levels of software.[133] The operating system may refer to the kernel program that manages the processes, memory, and devices. More broadly, the operating system may refer to the entire package of the central software. The package includes a kernel program, command-line interpreter, graphical user interface, utility programs, and editor.[133]

Kernel Program[edit]

The kernel’s main purpose is to manage the limited resources of a computer:

- The kernel program should perform process scheduling.[134] The kernel creates a process control block when a program is selected for execution. However, an executing program gets exclusive access to the central processing unit only for a time slice. To provide each user with the appearance of continuous access, the kernel quickly preempts each process control block to execute another one. The goal for system developers is to minimize dispatch latency.

- The kernel program should perform memory management.

-

- When the kernel initially loads an executable into memory, it divides the address space logically into regions.[135] The kernel maintains a master-region table and many per-process-region (pregion) tables—one for each running process.[135] These tables constitute the virtual address space. The master-pregion table is used to determine where its contents are located in physical memory. The pregion tables allow each process to have its own program (text) pregion, data pregion, and stack pregion.

- The program pregion stores machine instructions. Since machine instructions don’t change, the program pregion may be shared by many processes of the same executable.[135]

- To save time and memory, the kernel may load only blocks of execution instructions from the disk drive, not the entire execution file completely.[134]

- The kernel is responsible for translating virtual addresses into physical addresses. The kernel may request data from the memory controller and, instead, receive a page fault.[136] If so, the kernel accesses the memory management unit to populate the physical data region and translate the address.[137]

- The kernel allocates memory from the heap upon request by a process.[64] When the process is finished with the memory, the process may request for it to be freed. If the process exits without requesting all allocated memory to be freed, then the kernel performs garbage collection to free the memory.

- The kernel also ensures that a process only accesses its own memory, and not that of the kernel or other processes.[134]

- The kernel program should perform file system management.[134] The kernel has instructions to create, retrieve, update, and delete files.

- The kernel program should perform device management.[134] The kernel provides programs to standardize and simplify the interface to the mouse, keyboard, disk drives, printers, and other devices. Moreover, the kernel should arbitrate access to a device if two processes request it at the same time.

- The kernel program should perform network management.[138] The kernel transmits and receives packets on behalf of processes. One key service is to find an efficient route to the target system.

- The kernel program should provide system level functions for programmers to use.[139]

- Programmers access files through a relatively simple interface that in turn executes a relatively complicated low-level I/O interface. The low-level interface includes file creation, file descriptors, file seeking, physical reading, and physical writing.

- Programmers create processes through a relatively simple interface that in turn executes a relatively complicated low-level interface.

- Programmers perform date/time arithmetic through a relatively simple interface that in turn executes a relatively complicated low-level time interface.[140]

- The kernel program should provide a communication channel between executing processes.[141] For a large software system, it may be desirable to engineer the system into smaller processes. Processes may communicate with one another by sending and receiving signals.

Originally, operating systems were programmed in assembly; however, modern operating systems are typically written in higher-level languages like C, Objective-C, and Swift.[f]

Utility program[edit]

A utility program is designed to aid system administration and software execution. Operating systems execute hardware utility programs to check the status of disk drives, memory, speakers, and printers.[142] A utility program may optimize the placement of a file on a crowded disk. System utility programs monitor hardware and network performance. When a metric is outside an acceptable range, a trigger alert is generated.[143]

Utility programs include compression programs so data files are stored on less disk space.[142] Compressed programs also save time when data files are transmitted over the network.[142] Utility programs can sort and merge data sets.[143] Utility programs detect computer viruses.[143]

Microcode program[edit]

A microcode program is the bottom-level interpreter that controls the data path of software-driven computers.[144]

(Advances in hardware have migrated these operations to hardware execution circuits.)[144] Microcode instructions allow the programmer to more easily implement the digital logic level[145]—the computer’s real hardware. The digital logic level is the boundary between computer science and computer engineering.[146]

A logic gate is a tiny transistor that can return one of two signals: on or off.[147]

- Having one transistor forms the NOT gate.

- Connecting two transistors in series forms the NAND gate.

- Connecting two transistors in parallel forms the NOR gate.

- Connecting a NOT gate to a NAND gate forms the AND gate.

- Connecting a NOT gate to a NOR gate forms the OR gate.

These five gates form the building blocks of binary algebra—the digital logic functions of the computer.

Microcode instructions are mnemonics programmers may use to execute digital logic functions instead of forming them in binary algebra. They are stored in a central processing unit’s (CPU) control store.[148]

These hardware-level instructions move data throughout the data path.

The micro-instruction cycle begins when the microsequencer uses its microprogram counter to fetch the next machine instruction from random-access memory.[149] The next step is to decode the machine instruction by selecting the proper output line to the hardware module.[150]

The final step is to execute the instruction using the hardware module’s set of gates.

Instructions to perform arithmetic are passed through an arithmetic logic unit (ALU).[151] The ALU has circuits to perform elementary operations to add, shift, and compare integers. By combining and looping the elementary operations through the ALU, the CPU performs its complex arithmetic.

Microcode instructions move data between the CPU and the memory controller. Memory controller microcode instructions manipulate two registers. The memory address register is used to access each memory cell’s address. The memory data register is used to set and read each cell’s contents.[152]

Microcode instructions move data between the CPU and the many computer buses. The disk controller bus writes to and reads from hard disk drives. Data is also moved between the CPU and other functional units via the peripheral component interconnect express bus.[153]

Notes[edit]

- ^ A compiled program has each machine instruction ready for the CPU.

- ^ For more information, visit X86 assembly language#Instruction types.

- ^ introduced in 1999

- ^ Operators like

x++will usually compile to a single instruction. - ^ Note that this is despite the metaphor of a stack, which normally grows from bottom to top.

- ^ The UNIX operating system was written in C, macOS was written in Objective-C, and Swift replaced Objective-C.

References[edit]

- ^ «ISO/IEC 2382:2015». ISO. 2020-09-03. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

[Software includes] all or part of the programs, procedures, rules, and associated documentation of an information processing system.

- ^ a b Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 7. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Silberschatz, Abraham (1994). Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-201-50480-4.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 30. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

Their intention was to produce a language that was very simple for students to learn[.]

- ^ a b c Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 31. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 30. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 30. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

The idea was that students could be merely casual users or go on from Basic to more sophisticated and powerful languages[.]

- ^ a b McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ Bromley, Allan G. (1998). «Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, 1838» (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 20 (4): 29–45. doi:10.1109/85.728228. S2CID 2285332. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ a b Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ J. Fuegi; J. Francis (October–December 2003), «Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 ‘notes’«, Annals of the History of Computing, 25 (4): 16, 19, 25, doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887

- ^ Rojas, Raúl (2023-03-24). «The First Computer Program». arXiv.org. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Rosen, Kenneth H. (1991). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications. McGraw-Hill, Inc. p. 654. ISBN 978-0-07-053744-6.

Turing machines can model all the computations that can be performed on a computing machine.

- ^ Linz, Peter (1990). An Introduction to Formal Languages and Automata. D. C. Heath and Company. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-669-17342-0.

- ^ Linz, Peter (1990). An Introduction to Formal Languages and Automata. D. C. Heath and Company. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-669-17342-0.

[A]ll the common mathematical functions, no matter how complicated, are Turing-computable.

- ^ a b c McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ a b McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ McCartney, Scott (1999). ENIAC – The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World’s First Computer. Walker and Company. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8027-1348-3.

- ^ a b Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ a b Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 27. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 29. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b c Silberschatz, Abraham (1994). Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-201-50480-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Bill Pentz — A bit of Background: the Post-War March to VLSI». Digibarn Computer Museum. August 2008. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ a b To the Digital Age: Research Labs, Start-up Companies, and the Rise of MOS. Johns Hopkins University Press. 2002. ISBN 9780801886393. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Chalamala, Babu (2017). «Manufacturing of Silicon Materials for Microelectronics and Solar PV». Sandia National Laboratories. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ «Fabricating ICs Making a base wafer». Britannica. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ «Introduction to NMOS and PMOS Transistors». Anysilicon. 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ «microprocessor definition». Britannica. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ «Chip Hall of Fame: Intel 4004 Microprocessor». Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. July 2, 2018. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ «360 Revolution» (PDF). Father, Son & Co. 1990. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b «Inside the world’s long-lost first microcomputer». c/net. January 8, 2010. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ «Bill Gates, Microsoft and the IBM Personal Computer». InfoWorld. August 23, 1982. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ a b c Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ a b Stair, Ralph M. (2003). Principles of Information Systems, Sixth Edition. Thomson. p. 159. ISBN 0-619-06489-7.

- ^ a b Linz, Peter (1990). An Introduction to Formal Languages and Automata. D. C. Heath and Company. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-669-17342-0.

- ^ Weiss, Mark Allen (1994). Data Structures and Algorithm Analysis in C++. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 0-8053-5443-3.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Stair, Ralph M. (2003). Principles of Information Systems, Sixth Edition. Thomson. p. 160. ISBN 0-619-06489-7.

- ^ a b c Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 26. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 37. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Stair, Ralph M. (2003). Principles of Information Systems, Sixth Edition. Thomson. p. 160. ISBN 0-619-06489-7.

With third-generation and higher-level programming languages, each statement in the language translates into several instructions in machine language.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (1993). Comparative Programming Languages, Second Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-201-56885-1.

- ^ Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ a b Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 16. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 24. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 25. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 19. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b c d «Memory Layout of C Programs». 12 September 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1988). The C Programming Language Second Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 31. ISBN 0-13-110362-8.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 128. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ a b c Kerrisk, Michael (2010). The Linux Programming Interface. No Starch Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-59327-220-3.

- ^ Kerrisk, Michael (2010). The Linux Programming Interface. No Starch Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-59327-220-3.

- ^ Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1988). The C Programming Language Second Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 185. ISBN 0-13-110362-8.

- ^ a b Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1988). The C Programming Language Second Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 187. ISBN 0-13-110362-8.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 38. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 193. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 39. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 35. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 192. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ Stroustrup, Bjarne (2013). The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-321-56384-2.

- ^ a b Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 218. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 217. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Weiss, Mark Allen (1994). Data Structures and Algorithm Analysis in C++. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc. p. 103. ISBN 0-8053-5443-3.

When there is a function call, all the important information needs to be saved, such as register values (corresponding to variable names) and the return address (which can be obtained from the program counter)[.] … When the function wants to return, it … restores all the registers. It then makes the return jump. Clearly, all of this work can be done using a stack, and that is exactly what happens in virtually every programming language that implements recursion.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 230. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

- ^ Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. p. 240. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.